Chemistry 5.1 Endothermic and exothermic reactions

5.1.1 Energy transfer during exothermic and endothermic reactions

- The energy in the universe at before and after a reaction is the same.

This is known as the law of conservation of energy.

- This means that, because energy can only be transferred, reactions that

expel heat to the surroundings must end up with products that have less energy

than the reactants.

- This is known as an exothermic reaction.

- Exothermic reactions include combustion, neutralisation, and many oxidation

reactions.

- Everyday uses of them are for self-heating cans and hand warmers.

- The opposite of an exothermic reaction is an endothermic reaction.

- Endothermic reactions are when the products have more energy than the reactants.

- This causes the temperature of the surroundings to decrease, rather than

increase as it would in an exothermic reaction.

- Endothermic reactions include thermal decompositions and the reaction of

citric acid and sodium hydrogencarbonate. Some sports injury packs are based

on endothermic reactions.

Required practical 4: investigate the variables that affect temperature changes in reacting solutions

Aim: Investigate how different variables affect the temperature change produced by reacting solutions

(examples: acid + metal, acid + carbonate, neutralisation, displacement).

Key variables:

- Independent (examples to test): concentration of acid, mass of metal/carbonate, volume of reactants, surface area of solid, type of metal, initial temperature.

- Dependent (what to measure): temperature change (ΔT) of the solution.

- Control (keep constant): total volume of solution (unless volume is the variable), initial temperature, same container and insulation, same mixing/stirring method.

Safety:

- Handle acids with care; use appropriate PPE (goggles, gloves).

- Be cautious with reactive metals (e.g., sodium, potassium) and carbonates.

- Dispose of chemical residues according to local regulations.

Apparatus & reagents:

- Polystyrene cup or calorimeter

- Thermometer or temperature data logger

- Measuring cylinder

- Balance (if measuring mass)

- Stirrer

- Pipette (for precise volume measurement)

- Reactants: acids (e.g., HCl), metals (e.g., Mg, Zn) or carbonates (e.g., CaCO₃)

- Stopwatch or timer

Method (outline):

- Set up the calorimeter (polystyrene cup) with the initial volume of one reactant (e.g., acid).

- Measure and record the initial temperature of the solution.

- Add the second reactant (e.g., metal or carbonate) quickly, stir gently, and start timing.

- Record the temperature at regular intervals until it stabilises; note the maximum (or minimum) temperature reached.

- Calculate the temperature change (ΔT = Tfinal − Tinitial).

- Repeat the experiment varying the chosen independent variable (e.g., concentration, mass), ensuring to perform repeats for reliability.

Reliability & errors:

- Repeat each measurement until concordant results and use the mean ΔT.

- Minimise heat loss (use lids, insulation, work quickly).

- Sources of error: heat loss to surroundings, incomplete reaction, inaccurate temperature reading, assuming solution density = 1 g/cm³.

- Improve accuracy with better insulation, faster mixing, more precise thermometry, and using calorimeter corrections if available.

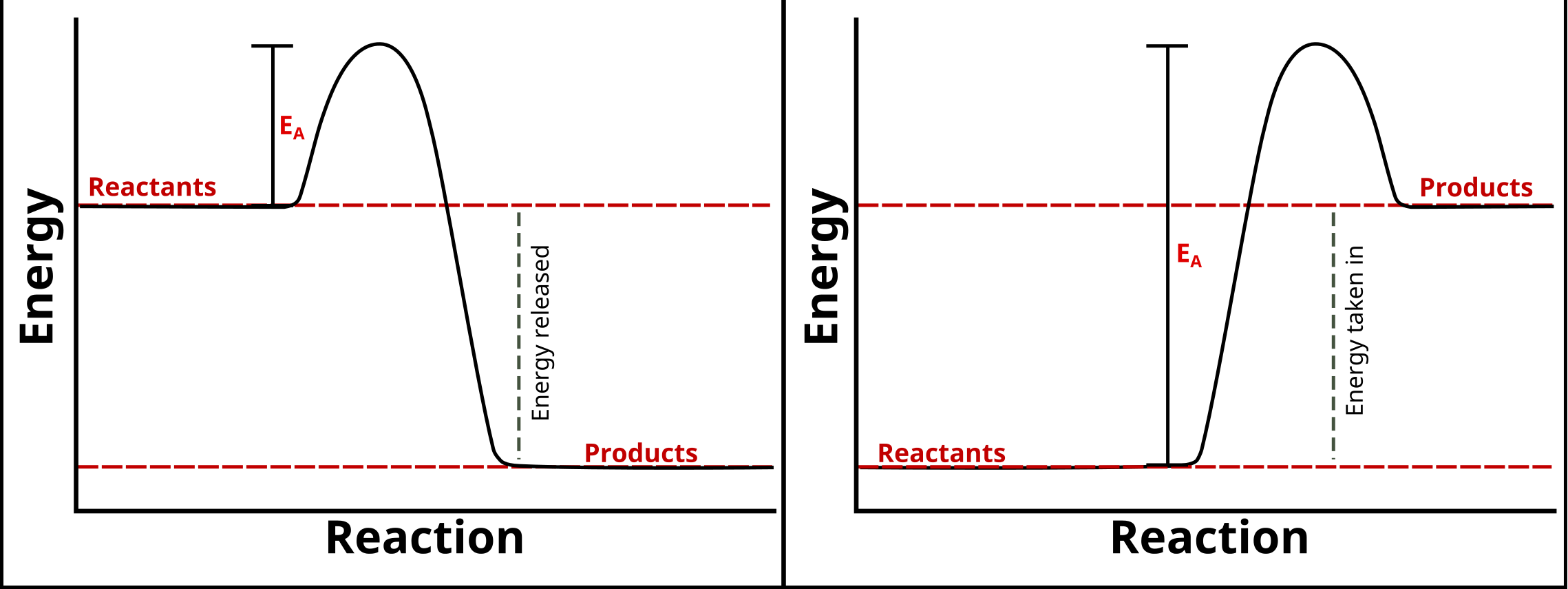

5.1.2 Reaction profiles

- Chemical reactions can occur only when reacting particles collide with

each other and with sufficient energy.

- The minimum amount of energy that particles must have to react is called

the activation energy.

- Reaction profiles can be used to show the relative energies of reactants

and products, the activation energy and the overall energy change of a reaction.

Energy Profile Diagrams (left is exothermic, right is endothermic)

source

source

- For the exothermic reaction, the energy of the products will be lower

than the energy of the reactants, so the change in energy is negative.

- For the endothermic reaction, the energy of the products will be higher

than the energy of the reactants, so the change in energy is positive.

5.1.3 The energy change of reactions

- Bond energy (or bond enthalpy) is the amount of energy required to break one mole of a particular bond in a gaseous state. Different bonds have different bond energies — for example:

- H-H bond in H₂: about 436 kJ/mol

- O=O bond in O₂: about 498 kJ/mol

- The difference between the sum of the energy needed to break bonds in the reactants and the sum of the energy released when bonds in the products are formed is the overall energy change of the reaction.

- In an exothermic reaction, the energy released from forming new bonds is greater than the energy needed to break existing bonds.

- In an endothermic reaction, the energy needed to break existing bonds is greater than the energy released from forming new bonds.

Bond Energy Calculations

The energy change for a reaction is given by this formula:

ΔH = Total energy to break bonds - Total energy to form bonds

- List the bonds in reactants and products.

- Look up the bond energies (usually given in the exam).

- Add up the bond energies for all bonds broken (reactants).

- Add up the bond energies for all bonds formed (products).

- Use the formula to find the overall energy change.

Example: Combustion of methane (CH₄ + 2O₂ → CO₂ + 2H₂O)

Bond energies (in kJ/mol):

- C-H:

412 - O=O:

498 - C=O:

805 - O-H:

463

Step 1: Breaking bonds (reactants)

- 4 × C-H =

4 × 412 = 1648 kJ - 2 × O=O =

2 × 498 = 996 kJ

Total energy needed to break bonds:

1648 + 996 = 2644 kJ Step 2: Forming bonds (products)

- 2 × C=O =

2 × 805 = 1610 kJ - 4 × O-H =

4 × 463 = 1852 kJ

Total energy released by forming bonds:

1610 + 1852 = 3462 kJ Step 3: Calculate energy change

ΔH = 2644 - 3462 = -818 kJ

Result:

The negative value shows an exothermic reaction (releases heat).